Night Riders and Hillbillies: The Kentucky Tobacco War

With all the recent legislation that aims to prohibit the use of tobacco among adult consumers, we often forget about the people caught in the middle: the tobacco farmer. The American tobacco farmer is the first link in the chain that stretches from the planted seed to the hand-delivered package that arrives on our doorsteps or the sealed container that we buy at the convenience store.

While the tobacco companies and the anti-tobacco coalitions make money hand over fist regardless of outside circumstances, the farmer is only as good as his crop. His laurels rest on what he can produce today, and what he can produce tomorrow.

A little over a hundred years ago, a literal war was fought in the tobacco growing hills of southwestern Kentucky and northern Tennessee, an area known as the “Black Patch”. All sides that participated have been viewed equally as heroes or villains, depending on who is telling the tale. I set out with this article to be as objective as possible, and to paint the events as they happened.

The ramifications of the war are still resonant today, but many people are unaware of this curious (and disturbing) chapter in American history. Let’s look back at what became known as the Black Patch War of 1906.

Hopkinsville, KY: 1900-1905

In my previous article, “The Real History of Snus in America”, I went into a bit about the American Tobacco Trust. This was the monopoly that controlled almost all tobacco production in America and most of England. Though the monopoly was later disbanded, during its active years it commanded a virtual stranglehold on all aspects of the tobacco industry.

This meant that the tobacco buyers working for American Tobacco were the sole purchasers of the majority of tobacco grown in this country. The larger the company that American Tobacco grew to be, the less they payed the tobacco farmer. If you were a tobacco grower in turn of the century Kentucky, you were left at the mercy of whatever the buyers that represented American decided to pay you for your crop. You either accepted their offer, or you went home with no money and a tobacco harvest that you had no other buyer to sell to.

By 1904, it had reached the point that American Tobacco was paying farmers less than the cost of planting the tobacco, and many families were going hungry. The Black Patch was prime tobacco land; little else would grow there. Tensions arose among the growers in the region.

Many of the farmers decided to band together to fight the Trust. The general idea was that if all of the tobacco farmers of Kentucky formed a union, they would have as much collective bargaining power as the tobacco companies. In 1904, The Planters Protective Association was born and within a week of its formation, nearly 6,000 tobacco farmers had joined.

This came as a shock to American Tobacco executives. They sent down “bullies” armed with sawed-off shotguns and pick-axe handles into the hills of western Kentucky to break down the opposition. They would arrive by the truckload, under cover of night, to a PPA member’s farm. They would proceed to set fire to the crops and destroy whatever farming equipment the family owned. If the farmer protested, he was usually tied up and whipped in front of his wife and children.

An even meaner breed of “bully” were the “hill bullies”. Hill bullies were local men recruited by the Tobacco Trust to go and terrorize their neighbors in the same violent manner as their union-busting predecessors. (The term “hillbilly” has its origins in the tales of the hill bullies.) Whereas a regular bully would only destroy what he found on your farm, a hill bully would go even further and destroy your hidden moonshine still, along with all of your bootleg whiskey. God forbid that you had any prior squabble with a hillbilly, for he was likely to take it out on your home by setting fire to it.

Some farmers were reluctant to join the Planters Association, citing the hillbilly attacks and night raids by Tobacco Trust “vigilante men”. These “scab” farmers were in turn courted by American Tobacco buyers who offered them high payments in exchange for staying out of the union. Many people began dropping out of the PPA now that the price for tobacco was on the rise.

1906

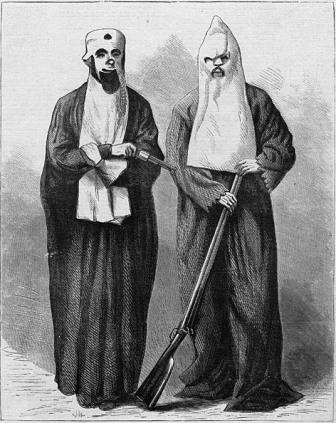

Watching their numbers begin to dwindle, the Planters Protective Association decided on drastic measures. A core group of influential men known to themselves as the “Inner Circle” began threatening men who refused to join the union (or members that intended on leaving), either with cryptic letters or late night raids on their farms. The letters were signed by the “Silent Brigade”, but to the public, they were known as Night Riders.

Partly through intimidation by union members, and partly in response to the Trust-backed hillbilly attacks, the ranks of the PPA doubled to approximately 11,000 members in the span of a few months. American Tobacco stopped trying to court non-union members, as they realized that there was no way that they could penetrate the PPA’s influence in the Black Patch. American Tobacco began to limit their purchasing of Kentucky crop by as much as they could stand, instead focusing on Maryland and western Virginia.

stopped trying to court non-union members, as they realized that there was no way that they could penetrate the PPA’s influence in the Black Patch. American Tobacco began to limit their purchasing of Kentucky crop by as much as they could stand, instead focusing on Maryland and western Virginia.

This left a lot of premium tobacco sitting around on the auction house floor, and soon word got out that you could get a good deal on prime leaf just for showing up after the American buyers left the auction. This brought the few independent tobacco companies that were still left in the US swarming over the hills of Black Patch.

The Night Riders didn’t take too kindly to the “carpetbaggers” that were diverting attention away from their battle with American. Independent buyers were run out of town or physically assaulted at auctions in an effort to keep small companies from cashing in on the situation. Instead, the independent buyers purchased from the few non-union growers still around. This infuriated the “Inner Circle”, who decided that it was time to escalate their actions.

In the course of a 48 hour wave of organized terrorist attacks, a group of two hundred Night Riders rode through the countryside laying waste to everything that they viewed as a threat to their union. Their first stop was a warehouse in the Black Patch that purchased non-union tobacco. They burned it to the ground and set fire to the adjacent factory. From there on they rode into the town of Elkton, where they blew up another non-union warehouse with a bundle of dynamite.

Their next attack was the most ambitious to date. As darkness fell on the night of December 06, 1906, the Riders crept into the town of Princeton. The two largest tobacco factories in the world were located there. Princeton served as the chief exporter of American tobacco to the whole of Britain. If you were an English tobacco user at the turn of the century, it was almost definite that your tobacco passed through the Princeton warehouses.

The Night Riders seized control of the town and set fire to all factories and warehouses that dealt in tobacco. Several townspeople were killed in the carnage. The Night Riders retreated back into the woods and proceeded to keep a lower profile for the next several months, as talk of their actions spread all over the South.

1907-1908

Exactly a year to the day of the Princeton attack, the Night Riders waged a full scale war on the town of Hopkinsville. Hopkinsville was thought to be too large a target for the Riders, and so it was very loosely guarded. Here is a description of the attack culled from various newspaper accounts of the day (author unknown):

The attack was made from the I.C. Depot. The masked men had left their horses on the outskirts of town and marched down 9th Street to Main where they separated into six squads and carried out their orders with military precision. Three men were sent to guard the Seventh Street bridge and small parties guarded other downtown streets.

A corral was formed at 9th and Main into which all citizens who ventured out were herded and guarded by a small squad. One squad went to the Cumberland Telephone office where they broke down the door, cut the wires and captured the two telephone operators on duty before they could sound the alarm.

Another unit surrounded the police station and shot through the walls and windows, quickly taking prisoner the men who were surprised inside. Other units took over the Fire Department and the L & N Depot. Small groups rode up and down the street shooting out windows wherever a light was turned on. I

n a very few minutes the city was in complete control of the masked men. The office of the newspaper, The Kentuckian, was vandalized and a buyer for the Imperial Tobacco Co., was dragged from his home and brutally beaten.

Another Account:

Three tobacco warehouses were burned during the raid on Hopkinsville, December 7, 1907. The largest squad marched to the Latham warehouse near the L & N Depot and then to the frame warehouse of Tandy & Fairleigh on 15th Street and burned them to the ground. The fire soon raged out of control destroying several residences, the Association Warehouse and threatening the Acme Mill. A railroad man was shot in the back when he tried to save some box cars from the fire. The leader of the night riders, Dr. Amoss, was accidentally wounded in the head by his own men.

At the conclusion of the raid the men assembled for roll call at the main intersection and then marched out of town singing “My Old Kentucky Home”.

A posse of eleven men was quickly organized and they were able to head off the retreating Night Riders, opening fire on the group. Reports differ as to how many Riders were shot in the melee, but at least one death and several injuries are certain.

The attack on Hopkinsville did not go unnoticed by the rest of the state. Armed militias were set up in tobacco towns all across Kentucky and Tennessee. The town of Russelville boasted that it wasn’t going to be threatened by a bunch of torch-bearing cowards in white sheets, and on January 03, 1908, the Riders attacked the town and torched its tobacco factories.

The governor of Kentucky decided to start cracking down on the Night Riders, and charges were brought against several of the men alleged to belong to the group. Not a single member was ever convicted of any crime. In most jurisdictions, the judges and prosecutors all belonged to the PPA. In other areas where the Riders did not have as looming a presence, potential witnesses were harassed, intimidated, attacked and sometimes murdered to prevent them from standing trial.

1909-1915

Night Rider attacks became more sporadic and isolated, and by 1910 had all but stopped. The Tobacco Trust was ordered to dissolve in 1911, and the PPA found itself without an enemy to fight. The organization was formally dissolved in 1915. Many of the Night Riders were instrumental in the reformation of the Ku Klux Klan that same year, but it should be noted that the original Night Riders did not hold any racist ideology or anti-religious beliefs.

The new Kentucky members of the KKK brought with them their old Night Rider uniforms, which was soon adopted by Klan groups nationwide. Though the Black Patch Wars were over, the white-hooded, torch wielding marauders found new enemies to fight. One of the largest Klan groups of today, the Imperial Knights of America, is based out of Dawson Springs, KY- stomping grounds of the original Night Riders. Indeed, many current IKA members boast of being descendants of the original Riders.

The Present

The Night Riders were as polarizing a group as any other in American history. Many modern day residents of the Black Patch view the Riders as heroes, and some of their deeds have achieved folk-tale like status through oral retelling of their exploits. Many view them as underdogs in the fight against Big Tobacco and corporate greed.

retelling of their exploits. Many view them as underdogs in the fight against Big Tobacco and corporate greed.

Others are unable to separate them from their acts of terrorism and violence. They were viewed by many (in their own time as well as today) as being no better, and maybe worse, than the people they were fighting against. Still others point to their eventual dissolution into the ranks of the KKK as evidence of their true intent.

As for the farmers that opposed the Association, they can be viewed as scabs that were willing to let everyone else’s family starve so that their own could eat. In reality, they were pawns played by both sides of the war. The Riders at first viewed them as mere cowards, then later as a genuine threat to their existence. Big Tobacco first tried beating them into submission, then tried stuffing their pockets full of cash in order to ingratiate themselves to the “heroic” picket crossers that refused to bow down to masked thugs on horseback.

And on the other side of the fence, we have the Tobacco monopoly. American Tobacco always feigned innocence for its part in the Black Patch Wars, claiming ignorance in spite of the overwhelming evidence against them. “We were just trying to buy tobacco, then the greedy farmers started trying to bully us into paying them exorbitant prices for their crops. We were friendly to the farmers who weren’t part of that evil union, and we paid them twice as much as all the other buyers were paying.”

That is the song that Big Tobacco has been singing for the last hundred years, and it’s a song that I’m sure they’ll be singing for the next hundred.

Stay tuned for my next article in which I take another look at early American snus history. Till next time,

R.R. Hubbard

SnusCENTRAL’s Resident Masked Man

About author

You might also like

Remembering Tom Dunn

As some of you may have heard, Mick and I have entered the publishing business with The Snuff Taker’s Ephemeris; a bi-monthly periodical devoted to all things snus and snuff.

A Lifetime of Nicotine Addiction

I still have an occasional pipe or cigar now and then. I went a long time without wanting them once I gave up cigarettes. I was afraid that the mere

Mayor Michael Bloomberg: The Reincarnation of Wilhelmus Kieft

Upon hearing the news of New York City’s ban on flavored tobacco products, I was immediately reminded of the tale of Wilhelmus Kieft, one of the first governors of what