Forget Camel SNUS: The REAL History of Snus in America

QUESTION: what do Red Seal American Snuff and Röda Lacket Swedish Snus have in common? ANSWER: At one time, they were one and the same!

To kick off my new column, I wanted to take a look over the course of the next couple of articles at the long history of snus in America. That’s right- snus in America. You may be surprised to learn that snus has been here almost as long as it has been in Sweden, and it didn’t just pop up overnight when RJR dropped the Camel SNUS bomb. The Swedes have been immigrating here, off and on, steadily for the last two hundred years, and they’ve always brought their snus with them.

To kick off my new column, I wanted to take a look over the course of the next couple of articles at the long history of snus in America. That’s right- snus in America. You may be surprised to learn that snus has been here almost as long as it has been in Sweden, and it didn’t just pop up overnight when RJR dropped the Camel SNUS bomb. The Swedes have been immigrating here, off and on, steadily for the last two hundred years, and they’ve always brought their snus with them.

Let’s flash back a bit to my last article, American Moist Snuff versus Swedish Snus. In it, I outlined the difference between snus and dip, with a focus on Copenhagen and Ettan, which were both introduced in 1822. If you’ll recall, Copenhagen was the first “dipping” tobacco manufactured in this country. It was derived from an old Scandinavian snus recipe. Unlike American dry snuff, the moisture content was pretty high in Copenhagen. The Swedes preferred their snuff “wet” since they wadded it up and put it under their lip.

Copenhagen wasn’t an overnight success by any means. In fact, it was pretty much impossible to find outside of Pennsylvania until the 1960’s. But that doesn’t mean that the rest of the country wasn’t busy dipping. In fact, many Americans were snusing! Let’s jump back to the beginning. In this case, our story starts in the early 1700s.

The Swedes were using snuff just like the rest of Europe. The unique thing about Swedish snuff was that it was more heavily “flavored” than other regional varieties. Much of the tobacco that came to Sweden ended up moldy during transit by sea. It was likewise hard to grow tobacco in most of Sweden, so it’s reasonable to think that a majority of Swedish tobacco was not “up to snuff”, so to speak. Most of it was flavored with common Swedish spices like Lingonberry, Juniper, Bergamot, Cinnamon, and Nutmeg. This was less to do with Swedes craving flavored tobacco and more to do with trying to make “green”, rotten tobacco even remotely palatable.

The oldest snus brand still in existence is Röda Lacket. In fact, it may be the oldest continuously made tobacco product period. It was introduced in 1753 by the Peter Schwartz factory. It slowly grew to be the most popular snus brand in southern Sweden before being launched nationally in the early 1800’s. It was one of, if not the, best selling brands (up until Ettan came along). It was also one of the first snus brand to be imported to North America.

In the US, the tobacco industry was still monopolized. All production was split basically between two different factions, the American Tobacco Company (smoking tobacco) and the American Snuff Company(smokeless). The American Snuff Company was a conglomerate of (former competitors) Helme, Weyman, Bruton, Beck, and Bolander. All during the 1800s, when these companies were in various stages of integration, there was experimentation with “snoose” tobacco, or, the strong oral snuff favored by Scandinavian immigrants.

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly where oral snuff originated in the US aside from Copenhagen, but it’s clear that different areas of the country had different snus brands in production prior to 1900. Some of these brands were called “snus” or “snoose”, and some were just labeled “snuff”, and some went by two or more different classifications depending which neighborhood/city they were sold in. In New Jersey, there was Viking and Norseman. In Pennsylvania there was Weyman/Copenhagen and Key (and by 1934, Skoal). But none of those hubs matched the production output of Chicago.

Chicago had a huge Swedish population and they brought their snus with them. In fact, the word “snus” was synonymous with Swedish culture in general. Neighborhoods, streets, buildings, and cities contained the word “snus or “snoose”: Snus Hill, Snus Junction, Snoose Boulevard, Snus Lake, etc.

Chicago had a huge Swedish population and they brought their snus with them. In fact, the word “snus” was synonymous with Swedish culture in general. Neighborhoods, streets, buildings, and cities contained the word “snus or “snoose”: Snus Hill, Snus Junction, Snoose Boulevard, Snus Lake, etc.

Seizing an opportunity, a New Jersey based company began to import some Swedish brands into Midwest markets. If you were a recent Scandinavian immigrant, the welcome sight of such familiar brands as Ljunglöfs Snus N.1 (later, just called Ettan), Blandning N.1, Ainkor, and Noorkopping would have made you feel right at home. If your English was pretty good, you would have recognized Röda Lacket masquerading as the anglicized Red Seal.

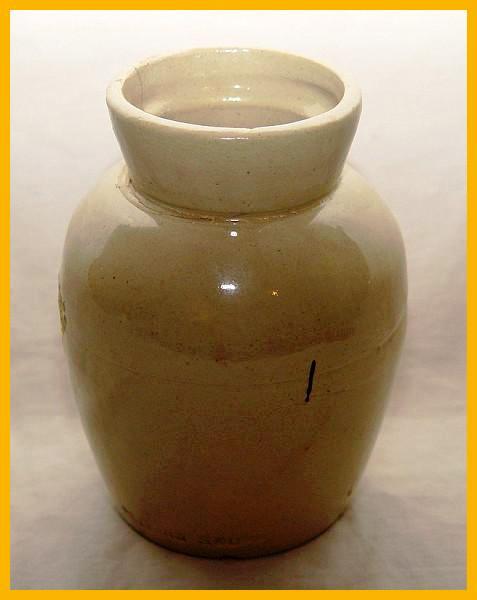

Red Seal was the first nationwide snus brand, whether anyone knew it at the time or not. Back before individualized containers of snuff/snus were commonplace, the tobacconist in your area would receive shipment of a large glass or ceramic jar with the company name labeled or embossed on it. Each company tried to make their container as distinct as possible in order to differentiate their product from the competition. (In fact, one of the very first trademark patents in this country was for a snuff brand).

commonplace, the tobacconist in your area would receive shipment of a large glass or ceramic jar with the company name labeled or embossed on it. Each company tried to make their container as distinct as possible in order to differentiate their product from the competition. (In fact, one of the very first trademark patents in this country was for a snuff brand).

Red Seal had a distinctive finch emblazoned on its jar, which the dry version still retains to this day. You would ask your store merchant for your weighted amount (generally an ounce or two) which he would put into a small burlap sack or, if you were somewhat well-to-do, your own personal snuffbox. Some companies furnished tobacconists with tobacco pouches stamped with their products trademark, or at the least, a small printed tag fashioned to the end of the drawstring with a logo printed on it. This practice later evolved into the selling of pre-filled tobacco pouches, and later, tins.

Red Seal was particularly popular in the southeast, where its mild sweetness bridged the gap between the heavy Scotches of the day and the overly sweetened Honey snuffs. Red Seal, being more moist and a courser cut than typical snuff, helped to popularize the “dipping” phenomenon in the south; a practice that was wholly inherited from our Swedish cousins. As stated earlier, it would be another hundred years before most of the country was privy to moist oral snuff, so Red Seal was as close as it got for the majority of the population. Somewhat overshadowed by the other snus brands available in the Midwest, Röda Lacket/Red Seal nevertheless remained a steady seller.

However, twenty years prior to the big tobacco monopoly being dissolved in 1915, Chicago had already started raising concerns about local tobacco producers being “muscled out” by the big East Coast distributors. The two big snuff companies, Helme and Weyman, decided to try and quell concerns in Illinois by inking exclusive distribution deals with local producers for some brands.

Therefore, Ainkorssnus became Anchor Snus once the Bollander company acquired the rights to it, and Blandning, Norrkoping, Röda Lacket and Grön Lacket (Red Seal and Green Seal) went to the August Beck Company. (Green Seal was an early wintergreen flavored snuff/snus that didn’t prove to be very popular at the time. It was another twenty or thirty years before Skoal became the first popular mint snuff). All of the other Swedish brands soon ceased importation. H. Bollander continued to manufacture Anchor snus clear into the 1930’s. (For the antique snus can collectors, white Anchor snus cans were manufactured prior to 1928, and the green label cans followed them.)

Therefore, Ainkorssnus became Anchor Snus once the Bollander company acquired the rights to it, and Blandning, Norrkoping, Röda Lacket and Grön Lacket (Red Seal and Green Seal) went to the August Beck Company. (Green Seal was an early wintergreen flavored snuff/snus that didn’t prove to be very popular at the time. It was another twenty or thirty years before Skoal became the first popular mint snuff). All of the other Swedish brands soon ceased importation. H. Bollander continued to manufacture Anchor snus clear into the 1930’s. (For the antique snus can collectors, white Anchor snus cans were manufactured prior to 1928, and the green label cans followed them.)

Beck & Co. had a slightly different distribution deal with their acquired rights. They were allowed to distribute them freely except for Red Seal, which was already a national brand. Therefore, they had the snus but they couldn’t call it Red Seal. They simply shortened the name to “Seal” and made sure that the logo was big and red. They also consolidated the Norrkoping brand by labeling the Seal snus as “Norkopping Svenskt Snus” on one side and “Seal Snuff” on the other side of the label. Later, they further consolidated the Blandning brand name in the same fashion.

already a national brand. Therefore, they had the snus but they couldn’t call it Red Seal. They simply shortened the name to “Seal” and made sure that the logo was big and red. They also consolidated the Norrkoping brand by labeling the Seal snus as “Norkopping Svenskt Snus” on one side and “Seal Snuff” on the other side of the label. Later, they further consolidated the Blandning brand name in the same fashion.

Without going into a great deal of of unnecessary political explanation, the tobacco monopoly was broken up and the smokeless companies were split into smaller units. This reversed the practice of trying to make some brands nationally known and went back into the older practice of trying to keep regionally focused. However, since these companies were once again in competition with one another, a lot of brand names were revamped or revitalized with an eye for bigger territory.

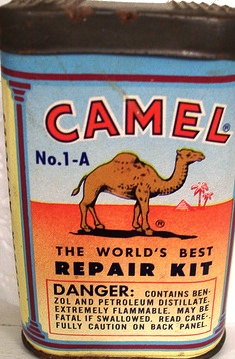

RJR for example had the rights to Camel, as did two other companies. The smaller company changed their version to “Kamel” with a K- which through a series of later acquisitions, RJ Reynolds found themselves owning both versions! (They reintroduced the “Kamel” line in the mid-nineties.)

The other company that owned the Camel name decided to use the logo for a brand of rubber tire patches that they manufactured. Similarly, Half and Half Pipe and Cigarette tobacco was a product blended with Lucky Strike and Buckingham tobacco. RJ Reynolds ended up with Half and Half, but not Lucky Strike or Buckingham, so they changed the familiar Lucky “bulls-eye” logo in the upper left hand corner to a generic “Burley and Bright” moniker. Lucky Strike went to American (later Brown and Williams, and now RJ Reynolds, who later sold their Half and Half to Pinkerton, who was absorbed by Swedish Match). Has your head exploded yet? Good. I won’t even go into what happened with Buckingham Cut Plug.

The other company that owned the Camel name decided to use the logo for a brand of rubber tire patches that they manufactured. Similarly, Half and Half Pipe and Cigarette tobacco was a product blended with Lucky Strike and Buckingham tobacco. RJ Reynolds ended up with Half and Half, but not Lucky Strike or Buckingham, so they changed the familiar Lucky “bulls-eye” logo in the upper left hand corner to a generic “Burley and Bright” moniker. Lucky Strike went to American (later Brown and Williams, and now RJ Reynolds, who later sold their Half and Half to Pinkerton, who was absorbed by Swedish Match). Has your head exploded yet? Good. I won’t even go into what happened with Buckingham Cut Plug.

This is more or less what killed Seal snus. Too many products changing hands and too many regional stipulations that were becoming redundant in the age of national expansion. The Red Seal brand weathered as many variations and evolutions as the market would bear, but by World War II, Red Seal had been homogenized into the rest of the United States Tobacco line as just another dry-style snuff. Thus it remained for the next several decades.

Flash forward to 1997. Now under the umbrella of the US Smokeless Tobacco Company, Red Seal moist snuff was “re-introduced” in America for the first time in almost seventy years. USST rolled the dice on two of their oldest snuff trademarks, Red Seal and Rooster, and tried marketing a low-priced dip brand under the same names. Rooster is now defunct as far as I know, but Red Seal still commands a respectable presence in the budget dip arena.

first time in almost seventy years. USST rolled the dice on two of their oldest snuff trademarks, Red Seal and Rooster, and tried marketing a low-priced dip brand under the same names. Rooster is now defunct as far as I know, but Red Seal still commands a respectable presence in the budget dip arena.

What’s interesting to me is the unique (among American dips) size of the Red Seal can. USST proudly advertises “20% More!” on the labels of Red Seal, as the can is slightly larger than the standard Copenhagen/Skoal shaped can. In fact, it’s the same size as your typical Swedish snus container. Perhaps a (coincidental) homage to the product’s roots? More on that later…

I hope you’ve enjoyed this little trip to the Snuseum. I had a blast compiling these notes and digging through old sales papers, brochures, and newspaper clippings. This article would not have been possible without the prior undertakings of noted snuser Rob the Clubman, nor without the historical research done in part by tobacco historian Billy Yeargin (I recently had dinner with those two, and let me say that I learned more about tobacco in one hour than I have in three decades.)

Janne Sunderling’s Snus history was an invaluable resource, as is the always fascinating Svensk Tobakshistoria. NONE of this would have seen the light of day had Larry Waters not kicked me in the butt and made me finish it!

Till next time,

R.R. “Feck” Hubbard

The World According to Feck

Writing for SnusCENTRAL.org

About author

You might also like

A Real Snus Review – 2011 Releases not all Great

Hello ladies and gents. It’s been quite a while since I’ve done a column here at SC, but we’ve been busy as sin trying to get the new issue of

Mayor Michael Bloomberg: The Reincarnation of Wilhelmus Kieft

Upon hearing the news of New York City’s ban on flavored tobacco products, I was immediately reminded of the tale of Wilhelmus Kieft, one of the first governors of what

Obama Hears a Help

Obama Hears a “Help!” A satirical poem by R.R. Hubbard (With apologies to Dr. Seuss) On the fifteenth of May, in the County of Cook,Swimming in the green pool of