Susan Ivey: Camel SNUS and Interview-Envy

Camel SNUS? I turn a blind eye for the WSJ interview of CEO Susan Ivey (sigh)

I don’t typically link to an entire article but this is an interview with Susan Ivey, CEO of Reynolds American (RAI) who I have been a not-so-secret admirer of for years. The US snus market has grown largely (and in many ways sadly) directly because of Reynolds American, Camel SNUS, and Susan Ivey. The Wall Street Journal estimates 18 million cans of various snus products were sold in the United States last year. In 2007 when I started writing about snus, their were only 4000 Swedish Snus users in the entire United States.

Times have changed and while the Camel SNUS product and the damage it continues to inflict on the taste-buds of new American snusers, there is no denying that the growth of American Snusers using REAL Snus from Sweden has a direct correlation to Camel SNUS advertising and marketing since SNUS was launched.

Myself included, a huge number of American smokers never even heard of snus until Reynolds. The flaw for Reynolds was Google. When I went on-line to learn more on what this snus-thing is, the search results revealed an entire world of Swedish Snus we had never heard of. To our amazement, snus was not invented by Reynolds or Philip Morris USA in 2006..it was invented in Sweden over 200 years ago and the first modern Steam Pasteurized snus was invented in 1822.

Myself included, a huge number of American smokers never even heard of snus until Reynolds. The flaw for Reynolds was Google. When I went on-line to learn more on what this snus-thing is, the search results revealed an entire world of Swedish Snus we had never heard of. To our amazement, snus was not invented by Reynolds or Philip Morris USA in 2006..it was invented in Sweden over 200 years ago and the first modern Steam Pasteurized snus was invented in 1822.

We also learned that Big American Tobacco snus is not made the same way as Swedish Snus. Swedish snus has been regulated as a Food Product since 1970. Today’s Swedish/Scandinavian snus is the absolutely least harmful tobacco product on the planet. Conservative estimates from the last 40 years of research and monitoring place Swedish Snus as at least 99% safer to a smoker than using cigarettes. In other words, about as dangerous as a cup of French Roast coffee.

Swedish/Scandinavian snus contains high levels of bio-absorbable nicotine (free nicotine) where American snus does not. American snus, dissolvable products like Camel Orbs and Camel strips, and Big Pharma alternatives like nicotine patches and nicotine gum are now marketed as a complimentary product to cigarettes. When you can’t smoke, snus or orb or patch. Swedish Snus is marketed and is a replacement product for cigarettes. The Swedish Government removed the requirement for a cancer warning label on Swedish snus a few years back….because Swedish snus doesn’t cause cancer.

With The Tobacco Act giving FDA the power to manipulate tobacco products to their own agenda with the help of Altria, whose lobbyist help write the Kennedy/Waxman legislation, and now the PACT Act about to become law which will decimate sales of Real snus directly from Sweden, the snus world is becoming a very uncomfortable place.

All that said, this article is about Susan Ivey (sigh) and her thoughts on the Reynolds smokeless products initiatives. For the purpose of this article, that’s all that really matters to me. My wife is standing behind me proof reading this, shaking her head and laughing.

Kudos and envy to David Kesmodel for getting to interview Ms. Ivey. So SnusCENTRAL.org isn’t The Wall Street Journal. Show off. Mr. Big Shot. Sorry, sour grapes. You’re one lucky bastard, Kesmodel!

LARRY WATERS

FORMER Smoker; CURRENT Swedish Snus User

Reporting From SnusCENTRAL.org

Smokeless Products Are Tough Test for Reynolds

R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company

R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company

WINSTON-SALEM, N.C.-During board meetings, Reynolds American Inc. Chief Executive Susan Ivey likes to suck on dissolvable smokeless-tobacco strips to get her nicotine fix.

She’s hoping to tempt millions of smokers to follow her lead.

Confronted with the inexorable decline of cigarette sales, Reynolds is transforming itself into a company that also offers an array of smokeless alternatives—including strips, lozenges and snuff.

D.L. Anderson for the Wall Street Journal

D.L. Anderson for the Wall Street Journal

CEO Susan Ivey says such items represent an important part of the company’s future..Still, they are apt to face tough marketing parameters under FDA rules.

Reynolds’ push into the products comes amid an intensifying debate among public-health professionals about how oral forms of tobacco should be regulated. Some tobacco-control advocates, including the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, have criticized Reynolds’ dissolvable products as nicotine candies designed to appeal to children.

Now the Food and Drug Administration is weighing in. It has asked Reynolds by Thursday to provide its research into how the dissolvable products are used and perceived by people 25 and younger. In a February letter to Reynolds, Dr. Lawrence Deyton, director of the agency’s Center for Tobacco Products, said the FDA is concerned that adolescents may be drawn to the products’ “brightly colored packaging” and “easily concealable size.”

The ruling will be one of the first for the FDA, which is in the early stages of structuring the framework under which it will oversee the production and marketing of tobacco products. Last year, President Barack Obama signed legislation giving the FDA sweeping powers to regulate the tobacco industry.

Reynolds says it is cooperating and that its products are marketed for adults and sealed in child-proof packaging.

Ms. Ivey, the company’s 51 year-old CEO, views the new lineup as a way to prepare Reynolds for a world that is likely to include fewer smokers.

“I believe these products can drive our sustainability into the future ,” she says. “Having a forward vision is important.”

In the process, she’s banking on support from scientists and public-health professionals who argue that lives could potentially be saved by encouraging smokers to switch to smokeless tobacco.

“It’s a disservice to public health if we keep products off the shelf that are [safer] than cigarettes,” says Scott Ballin, a longtime tobacco-control advocate who is the former legislative counsel for the American Heart Association. “To me, if we can come up with a better mousetrap, we should be considering those options.”

About one in five American adults smokes today, down from one in three in 1980, according to the Centers for Disease Control. At the same time, around 70% of smokers say they want to quit, says the CDC. Reynolds is trying to keep them as customers by offering a variety of smokeless products that deliver nicotine, the main addictive ingredient in tobacco.

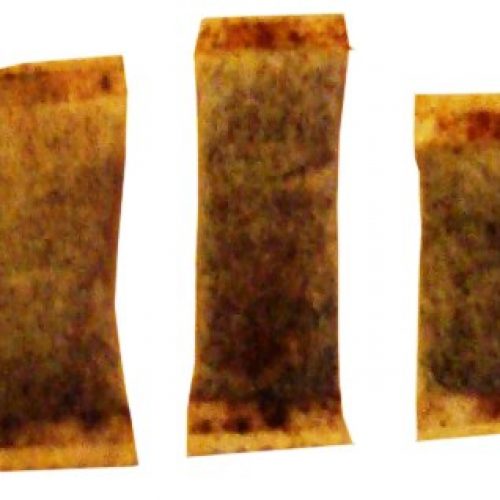

For a smokeless nicotine buzz, Reynolds offers Camel Snus, pouches of spit-free oral tobacco popularized in Sweden. The company is test-marketing Camel Orbs—tiny oval-shaped lozenges. Ms. Ivey’s own preference is for Camel Strips, thin tobacco wafers that melt on the tongue after three minutes. Reynolds also recently acquired Swedish company Niconovum AB for $43 million—the first move by a big tobacco concern to market smoking-cessation aids. And, of course, the 135-year old company plans to keep selling its Camel, Pall Mall and other cigarette brands.

The company has other reasons to look beyond the traditional drag. Reynolds, with 28% of the U.S. cigarette market, ranks a distant second to Altria Group Inc.’s Philip Morris USA, with 50%. Reynolds also has little exposure to cigarette markets abroad, where sales trends are better and restrictions often looser. Altria, too, is betting big on smokeless products. The company this month is rolling out Marlboro Snus nationally, after testing the brand in several cities. Last year it bought the maker of Skoal and Copenhagen moist snuff.

“There’s always two strategies: proactive and reactive,” Ms. Ivey says in an interview in her office at Reynolds’ headquarters here. “We’ve chosen a proactive path.”

The hurdles are high. Reynolds and other tobacco companies figure that only about seven million Americans use smokeless tobacco, although sales of those products are rising. Last year, sales volumes for smokeless tobacco products rose about 7%, while cigarette volumes fell about 9%, according to industry estimates.

A big challenge, as the FDA’s inquiry shows, is marketing the products. Although some groups, including the American Council on Science and Health, argue that smokeless tobacco is less harmful, and that smokers should be encouraged to switch to it, federal rules prohibit companies from marketing the products as a safer alternative to cigarettes.

Ms. Ivey, a smoker since college, is the first woman to run a major tobacco company. An extrovert, she sends congratulatory emails to employees who land promotions and is known to surprise low-level staffers by greeting them by name in the company cafeteria, say colleagues.

Her journey through the industry began by accident. In 1981, she was selling office equipment in Louisville when she called Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp. to complain that she couldn’t find its new cigarette—Barclay Menthol—in stores. The company happened to be recruiting salespeople and hired her a week later.

She scaled the ranks in sales and marketing and spent nearly a decade overseas for Brown & Williamson’s parent, London-based British American Tobacco PLC.

In 2001, Brown & Williamson, the No. 3 player in the U.S., named Ms. Ivey CEO.

After her years abroad, she says she returned to the embattled U.S. market “with fresh eyes.” Among other things, Ms. Ivey developed an interest in dissolvable-tobacco products.

In 2003, Brown & Williamson launched a test in Kentucky of a product called Interval, a dissolvable, mint-flavored smokeless tobacco lozenge the company had developed with an industry upstart, Star Scientific Inc. A year later, Brown & Williamson was acquired by R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Holdings Inc., and Reynolds canceled its pact with Star, saying the tests were unsuccessful. (Star, which sued Reynolds in 2001 in Maryland U.S. District Court over a separate patent issue, says it was surprised that Reynolds discontinued the project.)

Tapped as CEO of the newly named Reynolds American, Ms. Ivey embarked on a two-pronged strategy she called “total tobacco.”

This called for the company to dramatically reduce costs in its cigarette operations and invest part of the savings in the smokeless tobacco category.

She has cut Reynolds’ stable of cigarette products by nearly 600 items, or 70%, including “soft-pack” varieties of Kool, Winston and Doral. She outsourced payroll-processing and information technology and cut factory and white-collar jobs. Reynolds now employs about 6,400 people, 32% fewer than in 2004.

As Ms. Ivey was streamlining the cigarette business, she began to consider acquisitions in the smokeless tobacco arena. She made her first big move in 2006, buying Conwood Co., the maker of Grizzly moist snuff, for $3.5 billion.

That purchase was met with some resistance, as some executives worried the new business might distract management and further erode cigarette sales. “You could see it a lot through body language and conversations like, ‘You mean, we are not going to sell cigarettes anymore?”‘ says Chief Financial Officer Tom Adams.

“There is always fear in the boardroom: Are you taking the eye off where the money is today?” Ms. Ivey says. But she saw opportunity.

At the time, industry sales volumes for smokeless tobacco were rising about 6% a year, while cigarette volumes were falling about 4%.

U.S. retail sales of smokeless tobacco were about $5.2 billion in 2008, up 34% from 2005, and are expected to grow to $6.5 billion in 2010, according to market-research firm Euromonitor International. Smokeless options also offers higher profit margins, owing partly to lower tax rates.

Soon after buying Conwood, Reynolds said it would test-market Camel Snus, a type of spitless tobacco popular in Sweden.

Last year, Reynolds went national with the product, priced between $5 and $6 per tin, and began testing three dissolvable tobacco products—Camel Orbs, Strips and Sticks—in several metropolitan areas. Ms. Ivey says the products are more appealing to women than snuff and chewing tobacco because they don’t involve spitting.

Reynolds promotes them as options when lighting up is impractical or illegal.

Camel Snus, for instance, has advertisements in national magazines such as Maxim, encouraging readers to “Boldly Go Everywhere” with the “mess-free” product.

Matthew Myers, president of the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids in Washington, says most of Reynolds’ marketing of smokeless products suggests it is trying “to give smokers a mechanism for maintaining their addiction when they work in smoke-free locations,” which actually decreases “the incentive to quit.”

Ms. Ivey says she doesn’t think the products “are marketed in any way other than to give [consumers] choice.”

Reynolds says Camel Snus is showing promise, though sales are modest so far.

The entire U.S. snus market, dominated by the Camel brand, was about 18 million cans last year, less than 2% of the volume of the moist snuff market, according to Morgan Stanley analyst David Adelman.

Analysts say smokeless sales would get a big boost if Reynolds had FDA permission to promote Camel Snus and its other smokeless products as safer alternatives to cigarettes.

That isn’t likely to happen anytime soon.

The FDA has just recently set up various advisory committees that will make recommendations to the agency on how to decide what to do about various proposals, including reduced-harm applications.

According to the new federal tobacco law, companies must furnish scientific evidence that a product would reduce tobacco-related harm for individuals—and provide a net benefit to the U.S. population’s health.

Reynolds has come under fire for making such claims in the past. Earlier this month, a Vermont state judge ruled that the company had made false and misleading marketing claims— going back a decade—in marketing its Eclipse brand cigarette. During the industry’s unregulated era, ads had said the brand “may present less risk of cancer.” The company had said that its ads were “supported by credible and reliable information.”

About a year ago, Ms. Ivey and her board, which she chairs, began mulling another course of action. If the company was serious about giving tobacco users a full breadth of options, was it willing to offer them over-the-counter products to actually help them quit?

Tom Wajnert, Reynolds’ lead independent director, says some board members were “a little skeptical.” Eventually, he says, they agreed it was a “natural next step.” Global industry sales of over-the-counter smoking-cessation products are about $2.1 billion a year, according to Euromonitor International.

Ms. Ivey set her sights on Niconovum AB, a Swedish maker of nicotine gums, sprays and pouches that was founded by psychologist Karl Olov Fagerstrom, an expert on nicotine dependence.

Niconovum has sought to distinguish its over-the-counter products from conventional quit-smoking aids by delivering nicotine more rapidly and efficiently, helping users feel more control over their cravings.

Reynolds bought Niconovum in December for $43 million. Currently, Niconovum’s products are sold only in Sweden and Denmark. But Ms. Ivey says Reynolds is strongly considering filing for FDA approval to sell Niconovum’s products in the U.S., where they would compete with such products as Nicorette gum and Commit lozenges sold by pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline PLC. Makers of quit-smoking aids must prove in clinical studies that the products are safe and effective.

Ms. Ivey notes that Reynolds started more than a century ago as a maker of chewing tobacco—not cigarettes. “Who knows what the future holds?”

Write to David Kesmodel at david.kesmodel@wsj.com , the luckiest interviewer on Earth.

Bloomberg News

Bloomberg News